Written Task

List four key evolutionary design steps that contributed to the identity of your design culture today in your country in your opinion.

Movable type

Movable type originated in China around 1040 AD and made its way to Europe in subsequent centuries. The Latin alphabet, with its much more limited character set, was more suited to movable type than Chinese characters. Gutenberg held a short monopoly on the movable type and printing process in Mainz, Germany, until disagreements with investors meant that the process was in the public domain. His first major print work was the 42-line Bible in Latin, printed probably between 1452 and 1454.

William Caxton brought the printing process to England and set up his printing press in Westminster, London. According to one estimate, “by 1500, 1000 printing presses were in operation throughout Western Europe and had produced 8 million books” (Eisenstein, 1993)

From linotype and monotype machines to photo-print presses to desktop publishing, the industry has seen a remarkable move from a very specialist and labour-intensive process to a widespread and easier role that mostly happens in offices, in a relatively short time span. This has had a knock-on effect on the dissemination and reliability of information produced. My second uncle trained as a print apprentice for six years and was a type compositor in Bedford before he had to diversify his work to manage the changing industry.

As part of my Week 10 CRJ I went to St Bride’s Foundation and learnt how to set movable type and print on an Adana press.

Reference: E. L. Eisenstein: “The Printing Revolution in Early Modern Europe”, Cambridge, 1993, pp. 13–17, quoted in: Angus Maddison: “Growth and Interaction in the World Economy: The Roots of Modernity”, Washington 2005, p.17f.

Designs for the London Underground Map

Having lived in London for six years, and been a visitor for many more, how I move around the city is just as important as the places I travel to. London Underground has a brand that has become so strong that it is as much a part of London’s identity as physical landmarks such as St Paul’s and Big Ben. The map has to keep London’s residents informed of new lines and services (such as step-free access) in a clear and concise way, but also all of its millions of visitors who may not be used to cities or to English.

The first maps were drawn as early as 1907, and were the first to give equal weight to each line as well as giving each line its own colour. At this point, the lines were overlaying a geographical map of London and appear twisted and confusing compared to the current map.

In 1931, an employee of the London Underground, Harry Beck, realised that the physical locations of the stations did not matter so much as how they were related to each other. This led him to create a schematic map of the lines with the appearance similar to the layout of electrical circuits, although apparently, this was unintentional. The base of the lines is 45 degrees, compared to the 22.5 of other underground systems such as the Paris Metro, and by keeping this angle modern maps look visually very similar to the original map Beck designed.

Subsequent redesigns have retained the schematic plan, although some were better received than others as the spacing was more consistent over the map. Lines have been added in and the main tube map is free from the mainline railways not operated by TfL.

Station symbols have altered through the years: the original symbol for an interchange was a square and this was changed to a circle by Garbutt in 1963. In 2002, fare zones were added to the maps to clearly convey the ticket prices between stations for travellers.

The tube maps have inspired many alternatives, such as the walking tube map and the average rent tube map, and a good listicle of them can be seen on the TimeOut website.

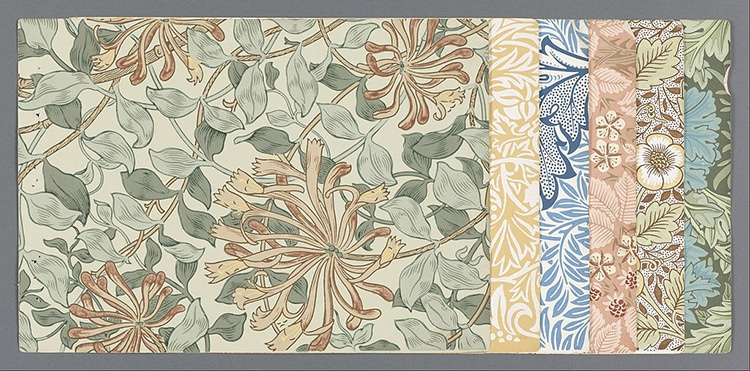

Arts and Crafts Movement 1850–1915

The Arts and Crafts movement was borne from a reaction to the effects of industrialisation and reformed the design and manufacture across the design world, from architecture to books. For all the excitement in new technologies emerging from the industrial revolution, to some, it felt like a dehumanisation of the creative process, especially because the quality of manufacturing was not particularly good.

The Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society, founded in 1887, was the naming inspiration for the movement, which was made up of many different arts organisations celebrating ceramic, textiles and furniture. It hosted exhibitions that were the only public platform for the decorative arts at this time.

The movement’s most notable practitioner is William Morris, who believed “passionately in the importance of creating beautiful, well-made objects that could be used in everyday life, and that was produced in a way that allowed their makers to remain connected both with their product and with other people.” (*)

William Morris is an inspiration to me because he reportedly learnt the techniques, such as Persian knotting for carpets, himself before teaching his employees the same techniques. This, to me, is a positive action of creativity and leadership and how I would like to lead the people that I work with.

Punk Graphics and Fanzines

Punk Graphics and Fanzines are a new area for me to research into, and I feel that they have contributed greatly to the British design aesthetic. Mark Perry is credited with creating the first punk fanzine, Sniffin Glue, in 1976 to report on what was happening as it was happening.

It feels essential to British humour to subvert the official communication channels, such as newspapers and books, and to create material that is irreverent and bold, because people didn’t feel as if they were represented in the traditional press.

The cut and glue, handwritten aesthetic reproduced on a photocopier allows for bold, unapologetic mistakes, and its accessibility to produce mean that everyone could create their own fanzine and to share their views with the world. In modern times, we have social media and young generations take advantage of the channels available to them to promote themselves and share issues that are important to them. However, the effort that it took to produce a zine is much more than the time taken to post online, and I think we are circling back to placing value on the time taken to produce work such as fanzines, or similar forms. From a cynical viewpoint, although people are making digital channels work for them, large publishers of content (such as Google and Facebook) make the most profit from these channels, whereas the punk graphics and fanzine movement did not have the overarching companies behind them. Except, perhaps, Xerox.